Symmetries, neural nets and applications - a quick introduction

Introduction to symmetries, equivariant neural nets and their limitations.

We awe and admire symmetries since at least prehistoric times.

So called Acheulean tools (see Fig. 1 below), crafted by a Homo Erectus since almost 2 million (!) years ago1, display a nice reflection symmetry, despite most likely, not adding any practical benefit.

Fig. 1: Prehistoric Acheulean tools are remarkably symmetric. Image source

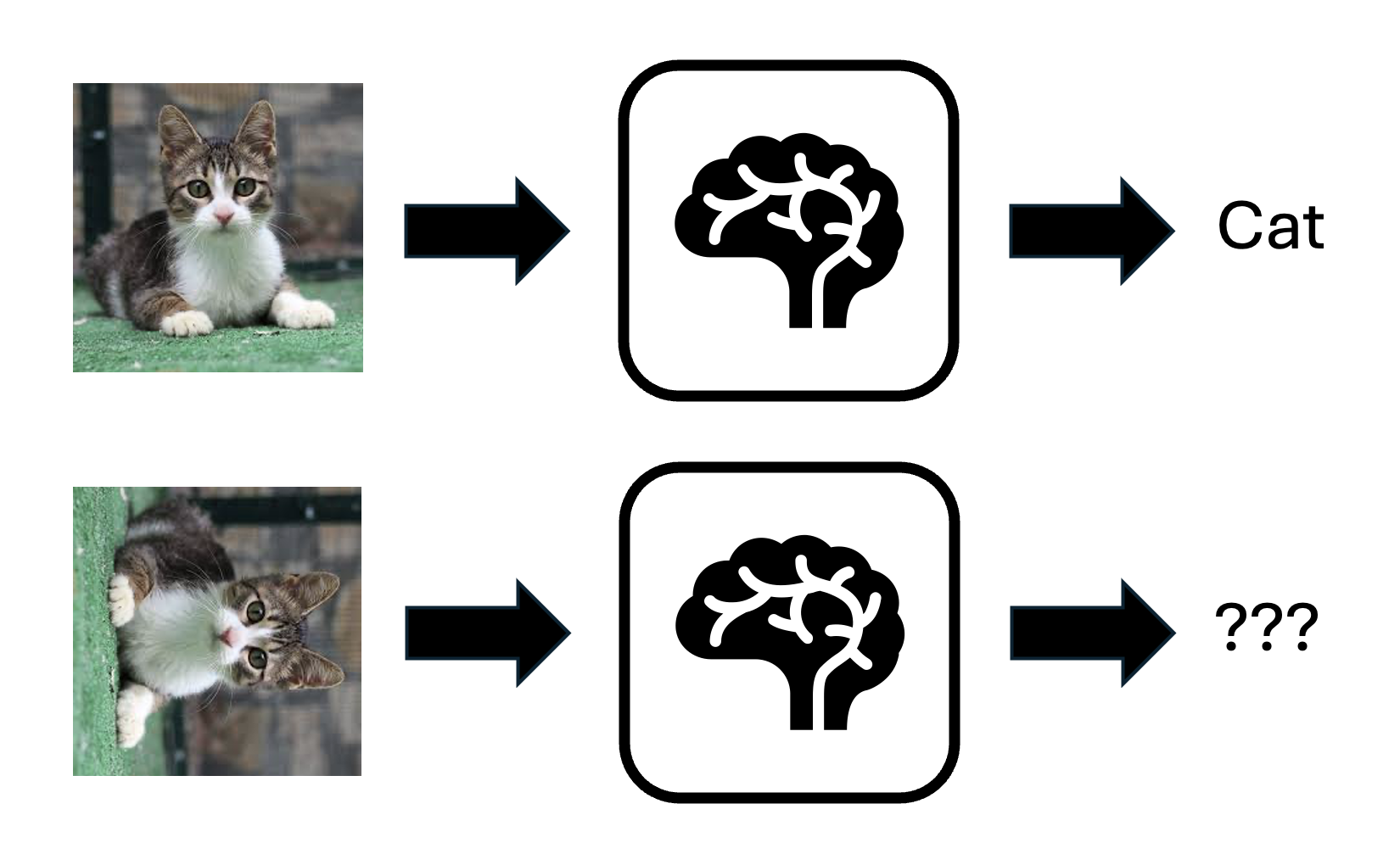

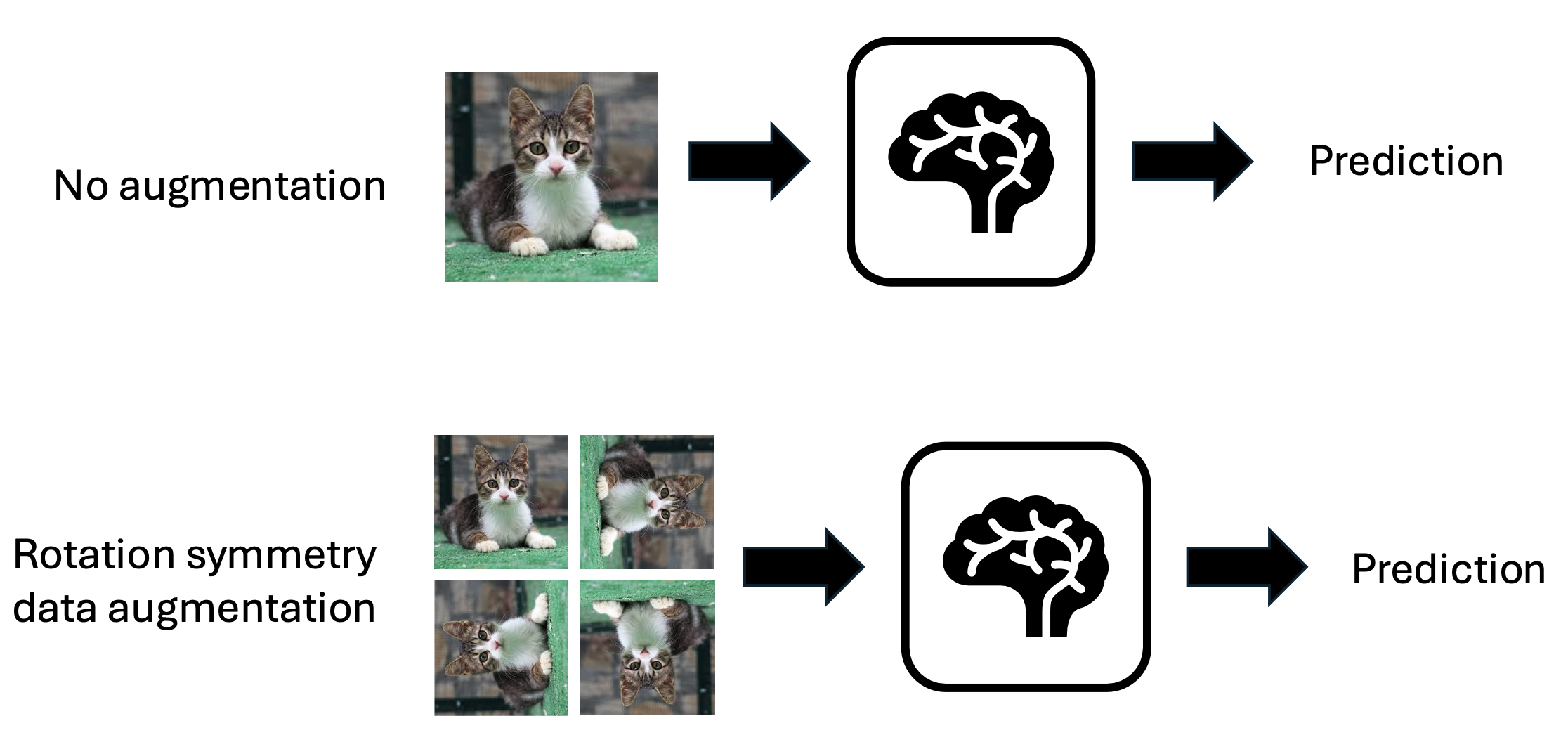

Beyond aesthetics, presence of symmetries signifies that an object “looks the same” under certain operations. For instance “we know” a square looks the same when rotated by \(90^{\circ}\). But does a neural network know? For instance, take a neural net used to distinguish images of cats vs dogs. Now suppose we rotate an image of a cat by \(90^{\circ}\)? Will the prediction of the neural network necessarily stay the same? A cat remains a cat under rotation right?

The answer is an astounding NO for a fully generic neural network architecture (see Fig. 2 for a little cat-cartoon).

Fig. 2: Generic neural nets can change their predictions under symmetry transformations such as image rotations.

That’s peculiar! Let’s patch things up by revising the question itself

Can prediction accuracy and robustness be improved if neural nets were symmetry-aware?

Well, the answer depends on the task.

While, as of early 2025, the application of “symmetric neural networks” to large language models remains limited2, the incorporation of geometric features (including symmetries) has proven invaluable in AI-driven scientific breakthroughs. Notable examples include the Nobel Prize-winning AlphaFold 2 model for protein folding and neural net models accurately predicting interatomic potentials.

Beyond molecular problems, quantum physics presents a particularly natural domain for geometric models, as the field is deeply intertwined with the concept of ‘symmetries’ in nature3. This connection gives me hope for the potential of symmetry-aware neural networks to tackle quantum problems, especially in the many-body context, where new symmetries often emerge. But is this optimism well-founded?

In the series of two blogposts, I will try to convince you that this is indeed the case. Initially, I planned to cover everything in a single post but quickly realized there’s just too much to unpack!

In this more ML-focused post, I’ll introduce symmetries in neural networks from a conceptual angle that I find to be the cleanest and most intuitive. Don’t worry — you don’t need prior knowledge of group theory or physics, just a basic understanding of linear algebra and machine learning. We’ll start gently in the next section by reviewing fundamental concepts like symmetries, groups, and representations, and then delve into the distinction between “invariance” and “equivariance” in transformations. Next, I’ll guide you through two leading methods for embedding symmetries into neural networks: data augmentation and equivariant neural networks. Finally, we’ll explore the limitations of these approaches, setting the stage for their application in the context of quantum many-body physics.

In the second blog post, we’ll build on this foundation, shift toward a more physics-centric perspective, and uncover surprising connections between symmetry approaches in physics and their rediscovery within the ML community. Exciting insights lie ahead, so let’s dive into the world of symmetries together!

- Symmetries&neural networks: from CNNs to symmetry groups and back

- How to explicitly teach symmetries to a neural net?

- Limitations of symmetric neural nets and possible remedies

- Outlook

- FAQ

- References

Symmetries&neural networks: from CNNs to symmetry groups and back

Let’s start from discussing 2D images. One of the early breakthroughs in image recognition was an invention of convolutional neural networks (CNNs): see e.g., [LeCun+ 1995]. Alongside advancements like “going deep” [Goodfellow+ 2016], much of their incredible success stems from structural biases embedded in their architecture. These biases reflect two fundamental properties of most images: reflecting two underlying properties of most images:

- Locality of information: Objects can often be recognized by hierarchically combining geometrically local features4.

- Translational symmetry in feature extraction: The location of an object within an image shouldn’t change its classification. To motivate this, the simplest example is the most cliche ever: cats vs dogs recognition. Fort this task it should not matter where the cat is on an image: a cat is a cat. This is not ensured in a generic neural network architecture: even if the network has correctly predicted a cat on an image, shifting it by some amount can switch a label to a dog - despite we know this just can’t be right!

Of course, this is just a very naive way of looking at things. A framework of geometric machine learning, formalizes many of the concepts related to symmetries and inductive biases for neural nets, such that we can study many more exotic symmetries than translations (special to CNNs). Let’s therefore try to be more precise. First, what do we even mean by translational symmetry, or symmetry more generally?

Symmetries and groups

Symmetry of an object is a transformation that leaves it invariant (i.e. the object does not change). The mathematical framework to capture symmetries is group theory5. Symmetry transformations make mathematical groups. Let’s do a simple example.

Symmetries of a square

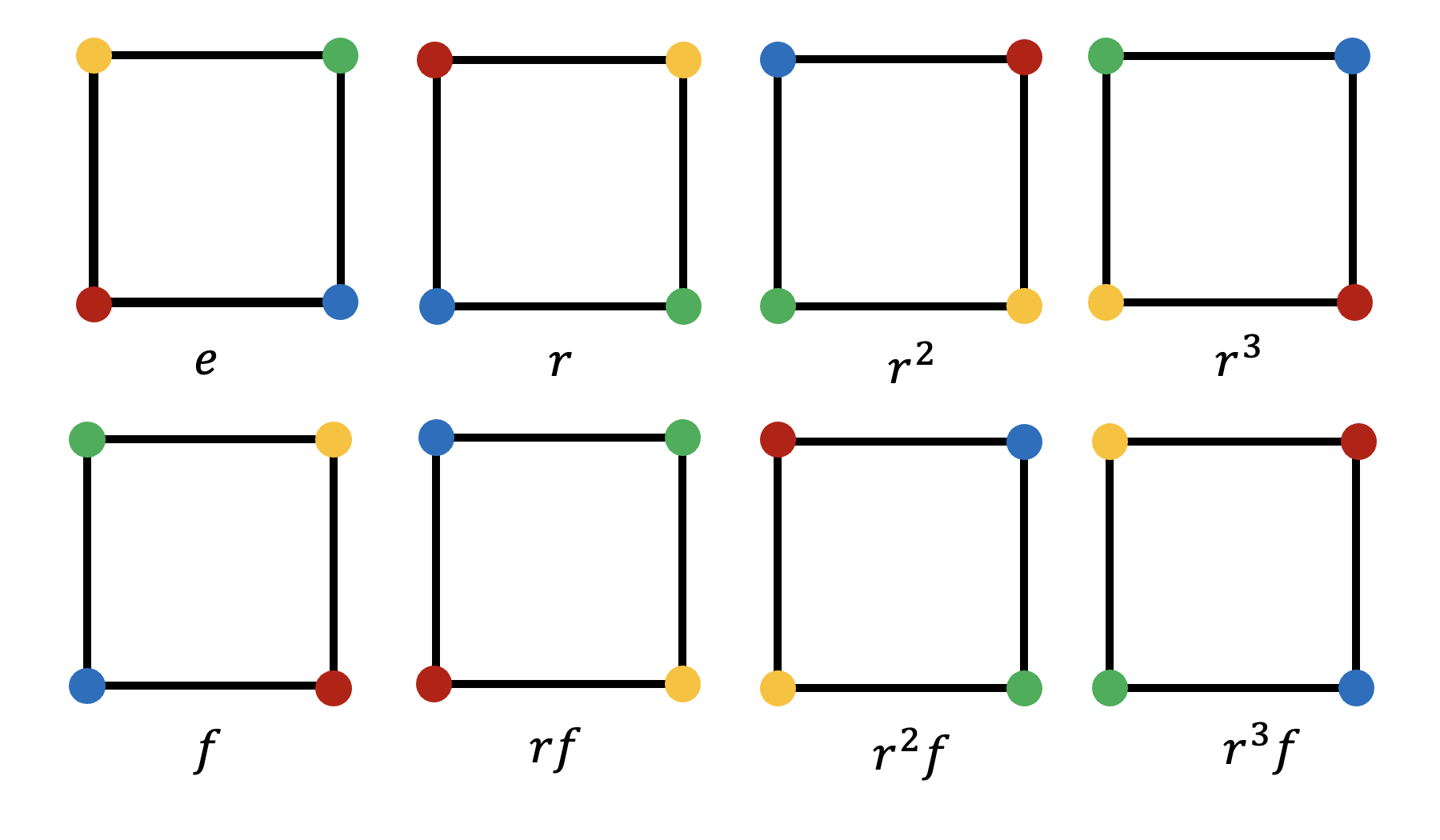

Consider a square. Rotations by multiples of \(90^{\circ}\) and flips of a square to make a \(D_4\) “dihedral” group (see Fig. 3). We can illustrate group properties here6

- Combination of symmetries gives other symmetries (closure): for example \(90^{\circ}\) followed by a \(180^{\circ}\) rotation gives \(270^{\circ}\) rotation which is also a symmetry.

- Existence of an identity operation: it means that there is an operation that does not rotate nor flip the square at all!

- Existence of an inverse element: if you want to “undo” rotation by \(90^{\circ}\), apply rotation by \(270^{\circ}\) to revert to the original position.

Thus for a \(D_4\) group we can explicitly write down the group elements \(G=\{ e, r, r^2, r^3, f, rf, r^2 f, r^3 f \}\) where \(e\) denotes identity operation, \(r\) represents a clockwise rotation by \(90^{\circ}\) and \(f\) a horizontal flip around centered \(y\)-axis.

Fig. 3: Symmetries of a square.

Notation comment: sometimes it is convenient to write down the group in the form of the group presentation \(G = \langle r,f \vert r^4=f^2=e, rf=f r^{-1} \rangle\) where we note down group generators which, when multiplied by other generators and themselves give all possible group elements (\(r,f\) are generators for \(D_4\)), together with a set of group relations i.e. constraints between different group elements \(r^4=f^2=e, rf=f r^{-1}\) above.

Upshot: Symmetries can be naturally described by group theory.

Groups and representations

Before we get back to the neural nets, let’s introduce another key concept: an idea of representation of a group. Mathematically, it is a (not neccesarily one-to-one) map \(\rho : G \rightarrow GL(N,\mathbb{R})\) from group elements to a (real) \(N \times N\) matrices, known as a general linear group \(GL(N,\mathbb{R})\).

This map assigns each element \(g \in G\) to a corresponding matrix \(\rho(g) \in GL(N, \mathbb{R})\), and it must satisfy the following property: \(\rho(g_1 g_2) = \rho(g_1) \rho(g_2) \quad \forall g_1, g_2 \in G\). This property is called a homomorphism, and it ensures that the group multiplication rule (closure) is preserved when working with the corresponding matrices i.e. combining two group elements in G corresponds to multiplying their respective matrices in the representation.

Intuitively, the reason we introduce representations is to make the abstract concept of groups more tangible by working with matrices. Matrices act on geometric spaces, allowing us to visualize and analyze group elements as linear transformations. This approach leverages the familiar and versatile toolkit of linear algebra, making it easier to explore and understand symmetries in a more concrete, hands-on way!

Now, for every group there are many possible ways of representing it. Let’s talk about some notable ones: a representation is trivial if \(\rho(g) = \mathbb{1} \ \forall g \in G\) and is faithful if \(\rho\) is one-to-one (i.e. every group element maps to a unique matrix in the representation). Another relevant representation is a regular representation of the group is that where all (\(\vert G \vert\)) group elements are represented as permutations on (\(\vert G \vert\)) elements.

It’s a bit abstract so let’s look at a simple example. Consider a \(\mathbb{Z}_d\) group \(G=\{ e, f, \dots, f^{d-1} \}=\langle f \vert f^d = e \rangle\).

- A trivial representation is just \(\rho(e)=\rho(f)=\dots=\rho(f^{d-1})=1\).

- A faithful, yet non-regular rep is \(\rho(j)=e^{2 \pi i j / d}\) where \(j\) enumerates group elements e.g., \(\rho(e)=1\), \(\rho(f)=e^{2 \pi i / d}\), …, \(\rho(f^{d-1})=e^{2 \pi i (d-1) / d}\).

- A regular representation (which is always faithful) has size \(d\) and corresponds to \(d \times d\) permutation matrices, which I display below for \(d=4\)

Upshot: A group of symmetries can be represented as matrices with different dimensions.

Some intutition: why can symmetries be helpful for neural nets?

Alright, enough about representations – let’s take a step back before diving into the details of incorporating symmetries into neural networks. Let’s play devil’s advocate: why should symmetries even help neural net predictions in the first place?

Here’s one extra intuitive perspective: the presence of symmetries in a problem implies a natural restriction on the hypothesis space that a generic, non-symmetric neural net would otherwise explore.

To unpack this idea:

- A typical neural network is free to explore all possible functions (or parameters) within its architecture, regardless of whether they respect the symmetries of the underlying problem.

- However, if we know a problem has inherent symmetries, we can safely ignore non-symmetric parts of the loss landscape. Why? Because we know the true solution must lie within the symmetric subspace.

By explicitly imposing symmetries on the neural network—such as through weight sharing (a concept we’ll explore in more detail in the later section)—we can significantly reduce the size of the hypothesis space. This in turn helps the network generalize better [Goodfellow+ 2016].

Equivariance and invariance

Great, now that we have a better sense of symmetries and why they’re useful for neural networks, let’s explore a concept that is quite popular in ML: equivariance with respect to group representations. What does it mean?

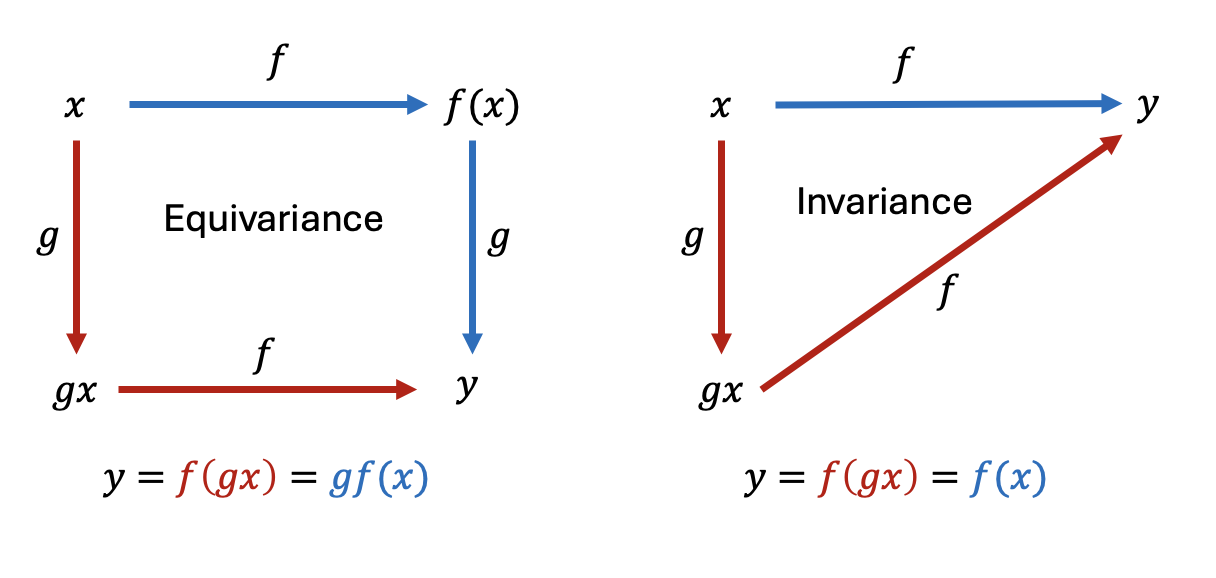

Physicists are super used to thinking about symmetry actions as transformations that leave an object invariant. For instance, translating an image of a cat by moderate amounts (ones not taking it outside of an image) shouldn’t change the label predicted by a neural network. Mathematically invariance means \(f(gx)=f(x)\) for all symmetry group elements \(g \in G\) from translational symmetry groups for an overall neural network represented as a function \(f: x \mapsto f(x)\). This means that applying a transformation \(g\) to the input \(x\) (e.g., shifting the cat) results in the same output as feeding the untranslated input directly into the network.

Let’s look inside the neural network though: in each layer \(k \in \{1,\dots,K\}\) it will extract some features, let’s say, eyes for simplicity. As we shift a cat on an image we would like the eye features to shift as well rather than stay put - in other words, we want such transformation to be “equally-varying with a cat” i.e. to be “equivariant” rather than “invariant”. It can be mathematically written as \(f_k(gx)=gf_k(x)\). Therefore, an equivariant neural network is typically built by stacking up layers, each equivariant under actions of a certain group: \(f_k(gx)=gf_k(x)\) for a neural net layer \(f_k\). Such series of equivariant layers would be typically finished by a final, invariant layer \(f_K(gx)=f_K(x)\) at the very end if the output of the neural net has properties of a scalar (e.g., it is a label).

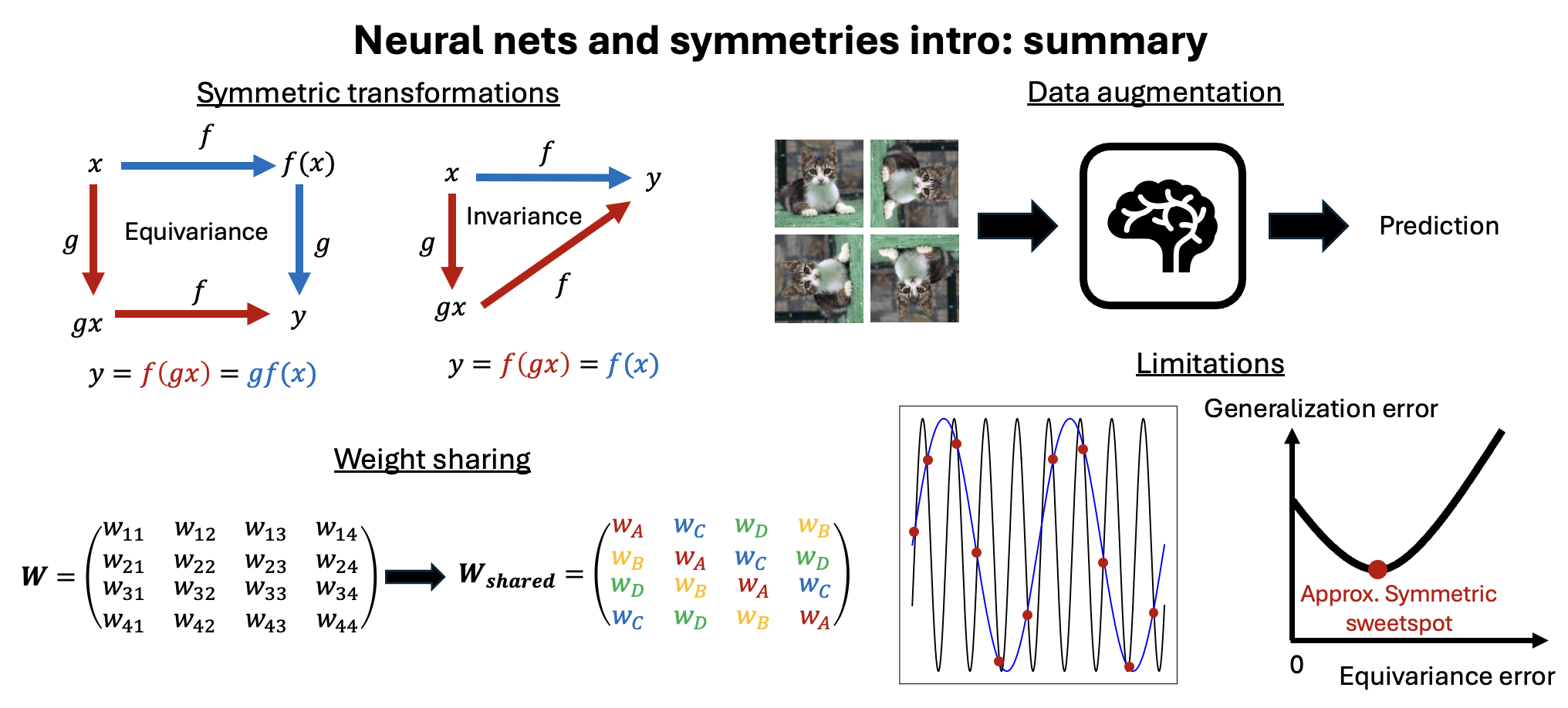

Let’s try to be slightly more formal to unconceal more. Consider the \(k-\)th layer of a neural network as mapping between two vector spaces \(V_{k}\) and \(V_{k+1}\) i.e. \(f_k: V_{k} \rightarrow V_{k+1}\). Let a symmetry group \(G\) act on \(V_k\) and \(V_{k+1}\) via representations \(\rho_i(g)\) and \(\rho_o(g)\) respectively. These representations may differ, particularly if spaces \(V_{k}\) and \(V_{k+1}\) have a different dimensionality. Now suppose we first act on \(V_k\) with a symmetry operation \(\rho_i(g)\) e.g., shifting a cat on an image \(x \in V_k\) by \(\rho_i(g)\). For equivariance we require \(f_k(\rho_i(g) x)= \rho_o(g) f_k(x) \ \forall x \in V_k \ \forall g \in G\) i.e. the output transforms under the same group of symmetries as the input (perhaps with a different representation though). This can be depicted as the diagram in Fig. 4 (left panel). Note that in this sense invariance is a special case of equivariance where we set \(\rho_o(g)= \mathbb{1} \ \forall g \in G\) i.e. outer representation is trivial: then \(f_k(\rho_i(g) x)= f_k(x) \ \forall x \in V_k \ \forall g \in G\) : see Fig. 4 (right panel).

Fig. 4: Handwavy way of writing so called “commutative diagrams” of equivariant and invariant transformations.

Upshot: Symmetric neural networks are typically constructed by stacking up equivariant neural networks layers.

A word of caution: CNNs are not fully translationally invariant?

Let’s take a quick intermission to complicate things further: contrary to popular belief, a typical CNN is not fully invariant under translation symmetry! This happens due to two factors:

- Aliasing effects: Subtle technical issues can arise when the input is sampled or processed, disrupting perfect translation invariance. We’ll explore this more in the section on limitations of symmetric networks.

- Final dense layer: The widespread use of a dense layer at the end of a CNN breaks equivariance. Dense layers generally depend on the spatial arrangement of features, so shifting those features typically changes the output, violating layer-wise equivariance7.

To make things even more intriguing, CNNs can often learn absolute spatial locations for objects—even when designed to be translationally invariant. This surprising behavior is discussed in this paper, which is worth checking out if you’re curious!8

How to explicitly teach symmetries to a neural net?

Good, now we know what do we mean by symmetries and recognize notions of symmetric maps corresponding to equivariance and invariance. We argued that we should stick to equivariant layers of the network for extracting features often followed by a final invariant layer. Now, how can one ensure that the neural network layer is equivariant? Broadly, there are two main approaches.

Data augmentation

In a data-driven setup, the simplest and often most cost-effective way to encourage symmetry in neural network outputs is data augmentation. If the data is symmetric under a group \(G\), we transform each example in the dataset using all possible transformations from \(G\), effectively expanding the dataset artificially (see Fig. 5 below for another cat-cartoon). The idea is that the neural network, when trained on these transformed examples, will learn to associate the input’s transformation with corresponding changes in the output. For unseen examples, it should generalize this behavior, ensuring equivariance in practice.

Fig. 5: A cartoon for rotation symmetry data augmentation.

This strategy has been surprisingly succesful and was recently applied e.g., within AlphaFold 3 [Abramson 2024+]. Symmetry-augmenting data only increases the training (but not evaluation time) with respect to baseline architecture by a factor of \(\mathcal{O}(\vert G \vert)\) (assuming we are talking discrete group here). Data augmentation also has some theoretical underpinning in terms of reducing generalization error: see [Wang+ 2022b] and [Chen+ 2019]. I should warn you, however, that this approach is data-centric and can’t be straightforwardly applied to non-data-driven problems. For instance, data augmentation does not directly apply whenever we use neural networks as a powerful optimization ansatze as in neural quantum states - since there is simply no data there! Therefore, when we turn to quantum many-body physics in the next blog post, we will need alternative methods for embedding symmetries into neural networks – one of which I will introduce below.

Upshot: Neural networks can be taught to be symmetric through data augmentation.

Weight sharing

Another approach, known as weight sharing, achieves equivariance by restricting the neural network architecture rather than augmenting the dataset. A particularly versatile method within this framework is the equivariant multi-layer perceptron (equivariant MLP), introduced by [Finzi+ 2021]. This method is quite general, working for both discrete and continuous (Lie) groups, and encompasses other popular group-equivariant frameworks, such as:

- G-convolutional networks [Cohen&Welling 2016],

- G-steerable networks [Cohen&Welling 2016b], or

- deep sets [Zaheer+ 2017]

These architectures are generalizations of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to symmetries beyond translations, making them powerful generalizations for a wide range of group structures.

The main idea of equivariant MLPs is very simple: to ensure that a linear layer of a neural network \(f: V_1 \rightarrow V_2\) is equivariant with respect to input and output representations \(\rho_i\) and \(\rho_o\) of the group \(G\), you constrain a general form of the weight matrix \(W\). Specifically, \(W\) must satisfy the following set of equations:

\(\rho_o (g) (W x) = W (\rho_i (g) x) \ \forall g \in G \ \forall x \in V\).

This equation enforces that applying a group transformation \(g\) to the input \(x\) produces the same result as applying the transformation to the output of the linear layer. The task is to solve this constraint for \(W\), ensuring that the layer is equivariant.

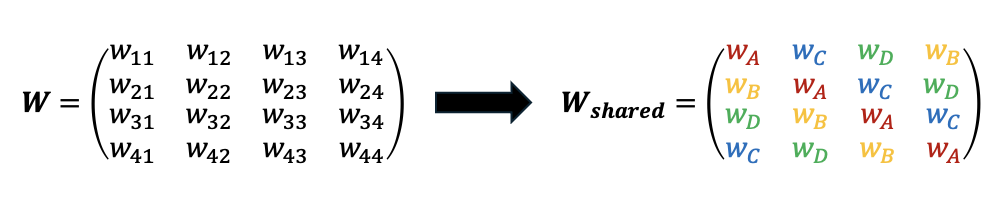

Let’s see equivariant MLP framework on a super simple example, which however demonstrates essential steps for solving many more difficult problems!

1D translation equivariance: linear layers

We will consider a regular representation of translational symmetry group of 4-pixel-wide 1D images. Suppose pixels can only be black or white (\(0\) or \(1\)) and we try predicting e.g., total parity of the input with a simple neural net (although it does not matter precisely what the task is!). The translation group presentation is \(G=\langle T \vert T^4 = \mathbb{1} \rangle\) i.e. the group has a single generator \(T\) fulfilling relation \(T^4=\mathbb{1}\). Thus for an \(N=4\) pixel image we have \(\vert G \vert = N\) and we will choose \(\rho_i = \rho_o \ \forall g \in G\) with the following representation of translation to the right by one element written as a \(4 \times 4\) matrix \[T = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}\]

Good, now consider any vector \(x\) in an input space \(V\). Following the prescription above we should write \(W T x = T W x \ \forall x \in V\) and similarily for all (non-identity) powers of \(T\) (corresponding to translations by more than 1 pixel). Since the expression needs to hold for all \(x \in V\) this means we can write simply \(WT = TW\) etc. which yields \[\begin{align} [W,T] &= 0, \\ [W,T^2] &= 0 \\ [W,T^3] &= 0. \end{align}\]

i.e. we require commutation of a weight matrix \(W\) with all of the group elements. It is straightforward to see that only one of these equations is independent and thus it is enough to demand \([W,T] = 0\). Is this to be expected? Yes, as we will see below from the complexity bounds of the method, this simplification is more general: computational cost of the method does not scale with \(\vert G \vert\) but instead with the number of generators; this is similar to G-steerable networks [Cohen&Welling 2016b] but in contrast to e.g., plain G-convolutional networks of [Cohen&Welling 2016]. Now going back to \([W,T] = 0\): for our case it can be easily solved for a general form of \(W\) under such constraints thus introducing weight sharing (see Fig. 6 below)

Fig. 6: Equivariance of a linear transformation can be thought within the framework of weight sharing.

To summarize: the interpretation is very simple: we want a linear transformation to be symmetric under certain group of symmetries and we appropriately restrict the weights of the matrix to belong to a few classes (here \(\textrm{# of classes}=\vert G \vert\)) within which the weights are shared, thus automatically fulfilling equivariance constraints!

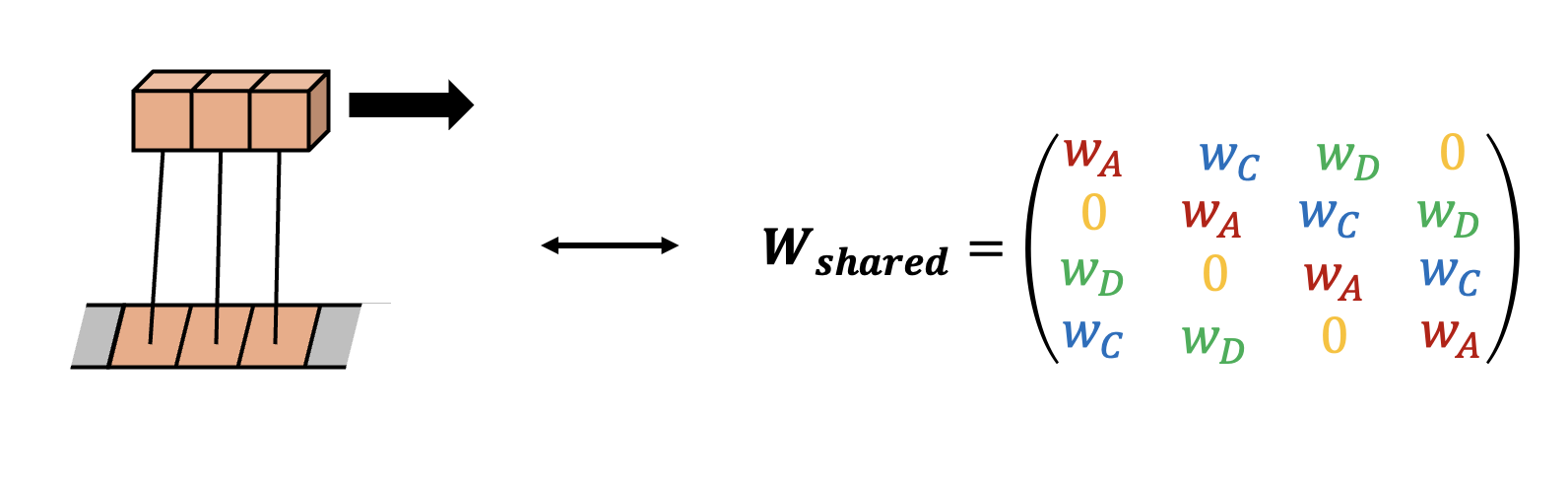

1D translation equivariance - how do they relate to convolutional nets?

I have motivated the use of symmetries partly based on the success of convolutional neural nets (CNNs) imposing translational symmetry. They can be thought as a special case of the weight sharing approach described above. A little reminder on convolutional neural nets: therein we use convolutional kernels (also known as filters) of size \(k\) acting on the 1D input data “image” \(x\) (a more usual case of a 2D CNN can be worked out similarily). To impose locality one would choose \(k \sim \mathcal{O}(1)\) and if we want it to span entire image globally then we would choose \(k = N\) (for a 1D “image” of size \(N\)). Since we want to delineate effects of locality and translational symmetry, we will assume the latter: each kernel will be of size \(k = N\) thus not imposing any notion of locality. Now CNNs work by shifting a kernel through an image (say to the right) with increments (known as a stride \(s\)) which we will assume to be \(1\) (to keep the dimensionality of the transformation with a goal of matching the weight sharing calculation from the previous section). This can be described by the following equation: \[y_i = \sum_{j \in \mathbb{Z}_N} w_{i} x_{i-j}\]

where \(w = \begin{pmatrix} w_1 & w_2 & w_3 & \dots & w_N \\ \end{pmatrix}^T\) is a kernel vector (of size \(N\) as described above).

After renaming the summation variable we get: \(y_i = \sum_{j \in \mathbb{Z}_N} w_{i+j} x_{i} = [W x]_i\) where in the final equation we stack up vectors \(w\) in the rows of the matrix \(W\) such that in row \(i\) they are shifted by \(i\) to the right (for \(N=4\)): \[W = \begin{pmatrix} w_1 & w_2 & w_3 & w_4 \\ w_4 & w_1 & w_2 & w_3 \\ w_3 & w_4 & w_1 & w_2 \\ w_2 & w_3 & w_4 & w_1 \end{pmatrix}\]

Does it look familiar? Yes! It is the same matrix we have obtained using weight sharing approach. It is straightforward to generalize this approach to an arbitrary value of \(N\) and for local kernels9 \(k \sim \mathcal{O}(1)\). The latter generalization can be found in Fig. 7. This formally establishes equivalence between convolutions in 1D and weight sharing in an equivariant MLP approach of [Finzi+ 2021]. This is a special case of a much more general statement regarding reduction of the weight sharing approach to well-studied group-convolutional neural networks of [Cohen&Welling 2016]. Nice!

Fig. 7: Equivalence of 1D CNNs with local kernels \(k=3\) and weight sharing matrix after imposing locality on the latter.

Upshot: For translational symmetry, weight sharing approach reduces to convolutional neural nets.

Non-linearities, biases and all that

Okay, so imposing equivariance is fundamentally about weight sharing. But you might argue: neural nets are affine transformations interspersed by non-linearities, and so far we have shown how to make only linear layers to be equivariant. Well, linear to affine generalization is easy: one can think of an affine transformation as a linear transformation in a higher dimensional space via an “augmented matrix”. This augmented representation incorporates the bias term as part of the linear transformation, ensuring that equivariance in the linear setting naturally extends to affine transformations.

How about non-linearities? In other words is it automatically true that \(\sigma(\rho_i (g) x) = \rho_o (g) \sigma (x) \ \forall x \in V \ \forall g \in G\)? Here the situation is much more subtle: for point-wise non-linearities (i.e. acting on each neuron separately e.g., SeLU, tanh etc.) and regular representations, any choice of such point-wise non-linearity preserves equivariance. Intuitively this is because regular representations of any group will only lead to a permutation of the neurons in a layer and therefore acting on neurons point-wise yields the same value as first acting with non-linearities and permuting afterwards.

However, when dealing with non-regular representations, choice of the non-linearity is much more restricted. Non-regular representations do not merely permute neurons; they may involve more complex transformations that cannot always commute with typical point-wise non-linearities. This means point-wise non-linearities may fail to preserve equivariance in this case.

For non-regular representations, we need to design non-linearities that explicitly satisfy the equivariance condition \(\sigma(\rho_i (g) x) = \rho_o (g) \sigma (x) \ \forall x \in V \ \forall g \in G\). The resolution, assuming unitary (or orthogonal) representations is to use e.g., norm non-linearities i.e. \(\sigma(x)= x \sigma( \vert x \vert^2)\) where \(x\) now is treated like a vector representing values on all neurons within the layer and does NOT act pointwise. Fulfillment of the equivariance condition comes from invariance (due to norm-preservation) of \(\sigma( \vert \rho_i x \rho_i^T \vert^2)=\sigma( \vert x \vert ^2)\) and equivariance of the \(x\) term in front of it. Furthermore, other choices of non-linearities are possible, e.g., [Weiler+ 2018] proposed using gated non-linearities or tensor product non-linearities.

Finally, I should mention that for some (not neccesarily regular) representations, point-wise non-linearities can still preserve symmetry in form of equivariance or invariance. A first step in theoretical understanding of this is provided by [Pacini+ 2024]. One of the interesting conclusions is that \(SO(n)\) - symmetric networks (\(SO(n)\) is a group of rotations in \(n\)-dimensional space) can be made at most invariant for most general point-wise non-linearities (but not equivariant)10.

Wrapping up: Limitations of equivariant MLPs

Equivariant MLPs provide a powerful framework for enforcing equivariance in neural networks, but they come with a few practical limitations. In practice, this approach is only limited by a relatively high \(\mathcal{O}((M+D)m^3)\) complexity of numerically solving for allowable weight matrix \(W\) where \(m\) is a size of an input (e.g., number of pixels in the image), \(M\) (\(D\)) is a number of generators of discrete (continuous) symmetries. In cases of very large images (and for symmetry groups which can be decomposed into product of translations and something else) G-steerable convolutions [Cohen&Welling 2016b] are probably a better approach. What remains curious is also an extra degree of freedom in constructing equivariant MLPs: while the representations of the input and output layers are typically determined by the problem (e.g., input data structure or output symmetry requirements), there is flexibility in choosing the representations for hidden layers. This extra degree of freedom raises questions such as are there any better or worse choices for hidden layer representations? For instance, does a degree of faithfulness of the representation matter? These questions remain open for further research and may lead to refinements in how equivariant MLPs are constructed.

Upshot: Symmetric neural networks can be constructed through weight sharing in linear layers and equivariant non-linearities.

Limitations of symmetric neural nets and possible remedies

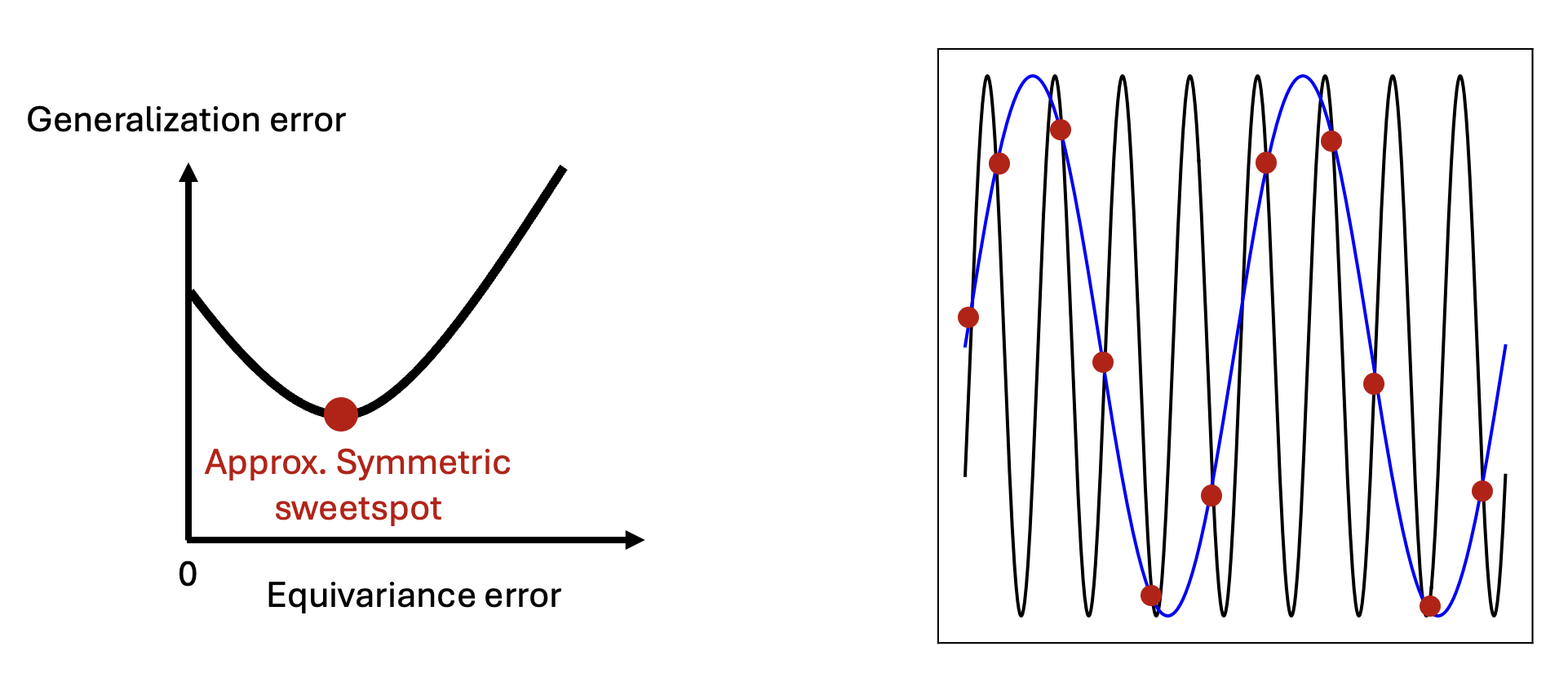

We have talked quite a bit about different flavors of teaching neural nets symmetries assuming a certain pristine setup (see Fig. 8):

Perfect symmetries exist in the data: The transformations are exact and cleanly reflected in the input.

Sampling theorem ignored: We haven’t accounted for practical limitations like finite resolution of images introducing a finite sampling rate which can be further changed in image processing.

Let’s try to relax these assumptions now and see if equivariance (even beyond equivariant MLPs studied above) can still be helpful!

Fig. 8: Two limitations of symmetric neural nets: non-fully symmetric data (left panel) and aliasing phenomenon (right panel).

Data symmetries are not perfect

World isn’t perfect right? Data isn’t neither. One way to address it is to relax requiring strict equivariance of models to only approximate equivariance. This amounts to requiring \(f(g x) \approx g f(x)\). The optimal level of symmetry violation can be figured out by the neural network itself. The simplest way of achieving it is simply through combining non-symmetric and symmetric layers within a neural network architecture (e.g., fully equivariant layers followed by non-symmetric layers). There also exist several more complicated constructions proposed in [Finzi+ 2021b] and [Wang+ 2022] which show advantages over simpler constructions on some datasets. In fact, we will see that requiring neural networks to be approximately symmetric instead of fully symmetric can be also highly beneficial for solving some quantum many-body physics problems. More on this in the next blogpost!

Upshot: Imperfectly symmetric data can be successfully studied with approximately-symmetric neural nets

Aliasing and equivariance

Wrapping up, here’s an intriguing fact: surprisingly, in many cases vision transformers (ViTs) without explicit symmetry encodings can be more equivariant than the CNNs which have the symmetries baked in! How come can it be the case? The culprit was already briefly mentioned in one of the earlier sections: it is the effect known as aliasing.

I will start by mentioning the obvious: our world, when projected to a plane, has continuous \(\mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}\) symmetry and not \(\mathbb{Z}_L \times \mathbb{Z}_L\) symmetric as assumed in CNNs applied to an \(L \times L\) image. In other words, a finite \(L\) means a finite image resolution and therefore instead of a full \(\mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}\) symmetry (where translation by any vector is allowed), we restrict ourselves to multiples of translations by 1 pixel only but not smaller11. More importantly, but in the similar spirit, when we downsample the size of the image (e.g., when using a stride \(s=2\) in a CNN) we break the \(\mathbb{Z}_L \times \mathbb{Z}_L\) group to a smaller one (e.g., \(\mathbb{Z}_{L/2} \times \mathbb{Z}_{L/2}\)).

What significance does it have? Well, it implies that only shifts which are multiples of the downsampling factor will keep CNN output equivariant [Azulay&Weiss 2019]. In this sense, in CNNs we are imposing often an incomplete group of symmetries. In fact, it was observed, to the surprise of many, that in multiple cases classification accuracy for a given image in a dataset is highly sensitive to shifts by certain vectors (not being a multiple of the downsampling factor i.e. shifts outside of our imposed group) thus breaking equivariance, yet insensitive to the others (multiples of the downsampling factor) [Zhang 2019]. Why does it happen? It can be explained through a concept of aliasing.

So what is aliasing? It happens whenever we undersample certain high frequency signal which appears then to us as a lower frequency signal (see Fig. 5, right panel). Frequencies come into the picture12 by thinking of a Fourier transform of an image: instead of representing information contained within an image in the real space we will think about it in a frequency space13. Finite resolution of an image introduces minimum \(-L/2\) and maximum \(L/2\) frequency in a discrete Fourier transform of an image. One can therefore think of images as if they were sampling continuous space with freqencies limited by \(f_s=L/2\). From Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem it follows that information in the true continuous signal is retained fully only if the image contained signals only below \(f_s/2\) (known as Nyquist frequency) and thus any information above that frequency may be lost through aliasing.

Summarizing, quite expectedly we lose information about continuous space by dealing with discrete images. What is, however, more surprising is that by the same argument we also lose information further during image processing with a CNN, all through aliasing phenonomenon:

- Within downsampling layers. This is because when we downsample \(L \rightarrow L/2\), by the sampling theorem, we are effectively losing frequency signal in range \((L/4,L/2)\).

- Within point-wise non-linearities. Why? Because, as shown by [Karras+ 2021], point-wise non-linearities (especially less smooth ones) often introduce more high frequency components to the image processing which can push the information beyond the Nyquist frequency14.

Quite naturally, aliasing also breaks equivariance as explicitly shown by [Gruver+ 2022]. Without aliasing, shifting by a vector \((v_x,v_y)\) in a real space corresponds to an extra phase in the Fourier transform15 \[G(f_x,f_y) \mapsto G(f_x,f_y) e^{-2\pi i(v_x f_x + v_y f_y)}\]

However, when signal is aliased then one instead applies \[G(f_x,f_y) \mapsto G(f_x,f_y) e^{-2\pi i(v_x \textrm{Alias} (f_x) + v_y \textrm{Alias}(f_y))}\]

which will apply incorrect shifts for frequencies \(f_x,f_y > f_s /2\) i.e. where \(\textrm{Alias}\) function acts non-trivially. One can directly link these incorrect shifts to introducing equivariance error as beautifully shown in a Theorem 1 of [Gruver+ 2022]. This also explains the earlier results [Zhang 2019] on CNNs respecting only shifts by multiples of downsampling factors.

Final remark: I should mention that phenomenon of aliasing extends well beyond translational symmetries. Similar behavior has been observed for other transformations, such as rotations and scalings, making aliasing a widespread challenge in symmetry-related tasks. People have figured out16 some architectural ways of mitigating aliasing effects by applying anti-aliasing filters [Zhang 2019], although, in practice, what matters the most for the improved equivariance is an increased model scale and dataset size [Gruver+ 2022]. In practice,the above-mentioned facts allow non-inherently symmetric architectures such as vision transformers to be more equivariant than CNNs (especially with extra data augmentations). However, as of early 2025, intrinsically symmetric networks still hold a significant advantage over transformers in many areas. In the next blog post, I will argue that this is especially true for various problems in quantum physics!

Upshot: Aliasing can disturb equivariance in the neural net through downsampling and non-linearities.

Outlook

I hope you have enjoyed reading about symmetric neural networks! We explored how symmetries are described as mathematical groups and represented by matrices. We distinguished between equivariance, suited for vector-like features (e.g., a cat’s whiskers should shift when the cat shifts), and invariance, appropriate for scalar outputs (e.g., the label “cat” remains unchanged after translation). We also discussed two key approaches to enforcing symmetries in neural networks: data augmentation and weight sharing. Finally, we covered their limitations—finite image resolution for weight sharing, and increased training cost and limited applicability for data augmentation. Phew, we have covered quite a bit of stuff — high-five for making it here!

In the next blogpost we will build on this foundational knowledge and explore how symmetric neural networks in ML connect to quantum physics, uncovering some fascinating parallels. Stay tuned!

FAQ

- How do I learn more about equivariance, along with a more rigorous mathematical treatment? For a good, simple, overview I would recommend reading this. For a more in-depth and rigorous (yet still pedagogical) treatment I invite you to read through an excellent Maurice Weiler book.

- The fact that CNNs are not so equivariant still puzzles me! Where can I read more? To read further about limitations of symmetric neural nets in context of CNNs and aliasing I highly recommend Marc Finzi’s PhD thesis as well as following papers: [Zhang 2019], [Karras+ 2021], [Azulay&Weiss 2019] and [Gruver+ 2022] as well as [Biscione & Bowers 2021], [Mouton+ 2021]; regarding approximately symmetric networks I recommend [Wang+ 2022].

- Which methods can I most feasibly apply to quantum many-body physics context? Excellent question, this is precisely the content of the second blogpost coming soon!

References

Abramson+ (2024) Abramson, J., Adler, J., Dunger, J., Evans, R., Green, T., Pritzel, A., Ronneberger, O., Willmore, L., Ballard, A.J., Bambrick, J. and Bodenstein, S.W., 2024. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature, pp.1-3.

Azulay&Weiss (2019) Azulay, A. and Weiss, Y., 2019. Why do deep convolutional networks generalize so poorly to small image transformations? Journal of Machine Learning Research, 20(184), pp.1–25.

Biscione & Bowers 2021 Biscione, V. and Bowers, J.S., 2021. Convolutional neural networks are not invariant to translation, but they can learn to be. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 22(229), pp.1-28.

Cohen&Welling (2016a) Cohen, T.S. and Welling, M., 2016. Group Equivariant Convolutional Networks. Proceedings of The 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning, 48, pp.2990–2999.

Cohen&Welling (2016b) Cohen, T.S. and Welling, M., 2016. Steerable CNNs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1612.08498.

Chen+ (2020) Chen, S., Dobriban, E. and Lee, J.H., 2020. A group-theoretic framework for data augmentation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 21(245), pp.1-71.

Finzi+ (2021) Finzi, M., Welling, M., and Wilson, A.G., 2021. A Practical Method for Constructing Equivariant Multilayer Perceptrons for Arbitrary Matrix Groups. Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, 139, pp.3318–3328.

Finzi+ (2021b) Finzi, M., Benton, G. and Wilson, A.G., 2021. Residual pathway priors for soft equivariance constraints. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, pp.30037-30049.

Goodfellow+ (2016) Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., and Courville, A., 2016. Deep Learning. MIT Press.

Gruver+ (2022) Gruver, N., Finzi, M., Goldblum, M. and Wilson, A.G., 2022. The lie derivative for measuring learned equivariance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.02984.

Karras+ (2019) Karras, T., Aittala, M., Laine, S., Härkönen, E., Hellsten, J., Lehtinen, J. and Aila, T., 2021. Alias-free generative adversarial networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34, pp.852-863.

LeCun+ (1995) LeCun, Y. and Bengio, Y., 1995. Convolutional networks for images, speech, and time series. The handbook of brain theory and neural networks, 3361(10), p.1995.

Mouton+ (2021) Mouton, C., Myburgh, J.C. and Davel, M.H., 2020, December. Stride and translation invariance in CNNs. In Southern African Conference for Artificial Intelligence Research (pp. 267-281). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Pacini+ (2024) Pacini, M., Dong, X., Lepri, B. and Santin, G., 2024. A Characterization Theorem for Equivariant Networks with Point-wise Activations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.09235.

Wang+ (2022) Wang, R., Walters, R. and Yu, R., 2022, June. Approximately equivariant networks for imperfectly symmetric dynamics. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 23078-23091). PMLR.

Wang+ (2022b) Wang, R., Walters, R. and Yu, R., 2022. Data augmentation vs. equivariant networks: A theory of generalization on dynamics forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.09450.

Weiler+ (2019) Weiler, M. and Cesa, G., 2019. General E(2)-Equivariant Steerable CNNs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32.

Zaheer+ (2017) Zaheer, M., Kottur, S., Ravanbakhsh, S., Póczos, B., Salakhutdinov, R.R., and Smola, A.J., 2017. Deep Sets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30.

Zhang (2019) Zhang, R., 2019, May. Making convolutional networks shift-invariant again. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 7324-7334). PMLR.

See e.g., this recent paper. ↩︎

This once amused me: I asked a top technical exec at a leading LLM company about their view on geometric machine learning (including research on symmetric neural nets), and their first response was: “What’s that?”. ↩︎

For instance, Hermann Weyl, a famous XX-century mathematical physicist once said “As far as I can see, all a priori statements in physics have their origin in symmetry”. ↩︎

A simple and perhaps naive example is the following: if you want to tell apart cats and dogs you would often want to extract geometrically located features such as whiskers (or their lack) or shape of the face. You would often then want to combine these features in a hierarchical fashion to produce the final label. By the way, condition on the data to successfully apply local kernels can be made more formally laid down by considering quantum enetanglement of the data: see this interesting work! ↩︎

If you have not studied group theory I highly recommend these excellent lecture notes! ↩︎

One extra property I am not mentioning here is associativity \((a \cdot b) \cdot c = a \cdot (b \cdot c)\). In most sane applications you will see this property to be automatically fulfilled. Some notable exceptions include group of octonions. ↩︎

On the other hand, global pooling operations at the end of the CNN such as ResNet50 would still keep that layer to be translationally invariant (see e.g., this for a simple proof). Oh, and skip connections are also equivariant, which is not hard to show. ↩︎

TL;DR: this effect can be attributed to image boundary effects! ↩︎

Given an equivariant solution for a weight-shared matrix, locality can be imposed by uniformly setting all connections further than \(k\) (in a geometric sense in \(n\) dimensions) to strictly \(0\) such that the kernel does not act there! ↩︎

Similar conclusion holds for any connected compact group. I thank Shubhendu Trivedi for pointing this paper out! ↩︎

Of course, in a relative sense translation by 1 pixel is the same for all linear image sizes \(L\). In an absolute sense, however, linear size of a single pixel scales like \(1/L\) and thus larger and larger \(\mathbb{Z}_L \times \mathbb{Z}_L\) becomes a closer depiction to a continuous reality. ↩︎

Pun not intended! ↩︎

In case you have not studied Fourier analysis before a good start is this 3Blue1Brown video. ↩︎

Intuitively you can think of the smoothness of non-linearity and new frequency introduction in the following way: take ReLU (which has a discontinuity in the derivative at \(x=0\)) and imagine you want to fit the sines and cosines to it around \(x=0\) (in a Fourier transform). To do it one needs extremely small spatial features implying very high frequency Fourier components. In contrast, smoother non-linearities such as swish introduce a much lower-centered frequency spectrum. ↩︎

In case this is not obvious: see time shifting property here. ↩︎

In fact as [Zhang 2019] points out, in the early days of CNNs (1990s) people were already aware of the downsampling issue and thus used aliasing-proof blurred-downsampling–average pooling operations. These approaches were abandoned later (2010s) due to better performance of max pooling which re-introduces sensitivity-to-small-shifts due to aliasing. Curious, how extra knowledge of theory on symmetric neural nets would be helpful back then! ↩︎